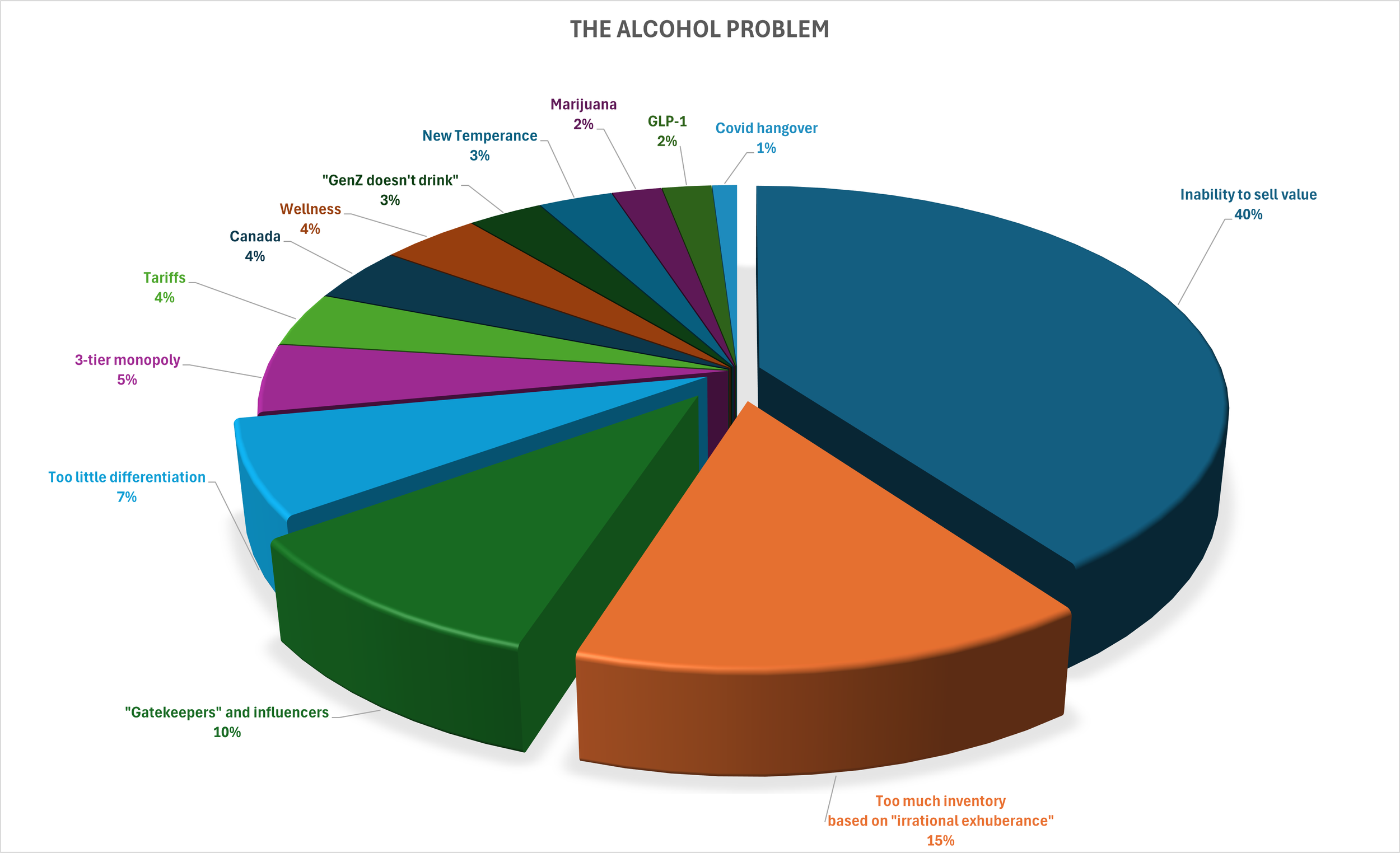

Percentages shown are for illustrative purposes only, they do not reflect an actual causal breakdown.

My personal view of what’s going on in the liquor industry in the first quarter of the 21st Century. Strap in, this will take awhile to unfold.

My background

January 9, 2026 marks my 17th year as a professional salesperson in the liquor industry. In that time, I wrote 2 books on whiskey, featured in other parts of this website; and taught the longest running whiskey class in the US, ending after 16 years. I don’t regard myself as an author, an expert or whiskey wizard. I’m a salesman who can articulate about my passion. For the previous 20 years, from the mid-1980s, I was a fanboy of Scotch whiskies, searching high and low for the rare bar or retailer that carried a selection of single malts, outside of the typical blends that dominated the category. During that time, I made a living in other vocations, first as an office furniture salesman; then a working actor in NY and LA (the product: me!); and then in the tech industry in multiple roles: IT Director, Customer Success Manager and a sales manager for multiple Silicon Valley startups during the “tech bubble” era. Long before that, as a younger person filling spots behind the bar or on the floor of a fine dining room, the idea of working in the liquor industry never once crossed my mind.

In January 2009, I was recruited into the liquor industry by an old friend who had a very elevated position in the liquor distribution tier, a 3rd generation liquor man. He had a revolutionary approach to a problem: I was to become a “brand ambassador”, but with a twist. More about that later.

Background:

The role of the brand ambassador goes back to the post-war “MadMen” era of liquor firms: National, Seagram, Hiram Walker, American Distilling, et. al. In those days, they were known as the “Missionary Good Will Men” and were co-funded by each firm’s distribution partners. The Don Draper team format was the current business standard: a senior manager led a team comprised of both account and creative peoples. At that time, they were two sides of the same coin: different roles, same goals. The Good Will Man was part of the team with one foot in each role, responsible for education, adoption, advocacy and re-order.

However, the introduction of computer-generated data into the business atmosphere in the late 1960s disrupted this team approach. Data became everything, and a new generation of data-driven analysts created a separate entity: marketing. Marketing analyzed the data, formed the strategy, created the program. They stuck close to the office, influencing the decision makers and eventually moved into the C-suite themselves. The “creative” teams came under their purview, at their whim. The “account” people became merely “sales”, sent into the street to execute marketing programs with little input. This was the format across all business for the next 50 years as the wall between the two became wider and more impermeable, never directly communicating until the quarterly number came in, and then only to blame the other if it wasn’t good.

Deep Background:

The term “ambassador” came about in the 1990s. Madison Avenue continued to be the dream merchants of the consumer culture and was only blocks away from a powerful entity that infiltrated the cultural, social and political life of New York City: The United Nations. Populated with Ambassadors, envoys and charge d’affairs from far off lands, they advocated for and taught about their native cultures and geographies, each an exotic outpost for the mid-century American with only a soldier’s understanding of world geography. The creative minds behind consumer brands borrowed this idea of an exotic advocate, not for the virtues of a country or a people, but of a brand, and the “brand ambassador” was born.

The Evolution

The brand ambassador role went to sleep during the downturn of whiskey in the 1970s and 80s. When it returned in the 90s, the entire business landscape had changed. Sales and marketing were now on 2 different journeys. In the liquor industry, there came a fateful turn. In the early years of the 21st century, a group of young people were recruited by an American marketing agency to spread the understanding and joys of Scotch whisky, specifically, the single malts that went into the Johnnie Walker blend. The single malts were first marketed as Classic Malts, and the young “Masters of Whisky” (as they were labelled), were spread out through the next two tiers (distributors and the trade) as well as the higher-echelon consumers (Wall Street, etc) to teach them about all things Scottish: pot stills, Highlands, kilts, malted barley and something called the “5 regions of Scotch whisky”. They conducted pairing dinners, in-store tastings, attended whisky festivals and made continuous appearances on behalf of their brand. They introduced tasting notes like “Christmas cake” and “marzipan” and were ubiquitous at a time when the idea of drinking whisky suddenly became fashionable amongst a new generation. At this same time, the classic cocktail re-emerged from its 70-year hangover, further pushing the desire, and need, for another way of drinking. As a result, the idea of a “brand ambassador” for an alcoholic drink caught on like wildfire throughout the industry.

And not only whiskey companies, but gin, vodka, rum and every other type of spirit brand competing for space on a shelf, in a bar or in the consumer’s head. The new breed of bartenders who adopted the classic techniques and recipes became the breeding ground for the next wave of ambassadors, which continues to this day. This is where it started to go off the rails. Too many people out in the marketplace with incomplete, generic knowledge pushing products on a generally clueless population. All were eager to learn, all were eager to be led on as well. It was a vibe and vibes are difficult to control.

As a distributor, essentially the default sales organization, my friend’s intimate knowledge of the brand ambassador’s role led him to understand that it was the most under-utilized position in the industry. The reason: a BA was purely marketing and disconnected from the sales process. Being a marketing “program”, they were subject to the whims of the corporate marketing managers and their ability to secure dollars from the company’s operating budget, writing up elaborate and obscure objectives of what the brand ambassador’s role was, and filing them under the heading of “KPI”: key performance indicators. KPIs were a list of objectives that the ambassador had to meet in the performance of their jobs: numbers of tastings, numbers of trainings, numbers of consumer events. But also, metrics on expense tracking, time management and more. The one thing left out: how many sales were made and how much product was sold. This was outside the ambassador’s purview, falling solidly inside the sales organization. In the best of scenarios, which were few and far between, they worked hand in hand; but for the most part, they were completely divorced from each other. Most of the time, the ambassador was outsourced to an outside agency that had its own KPIs, none of which had to do with selling. As one high-level manager told me, “We’re basically just managing their calendars so we can justify the marketing program expenses”. A whispered complaint from a long-time ambassador: “I do staff training after staff training, but there’s no record of me moving bottles”. Here lay the root of the problem: marketing teams that had never met a customer or spent a day in the field were creating programming for the marketplace. Sales teams were out in the field and had no say in the creation of the programming; divorced from the nuances of each brand, they merely laid down a set of numbers directed by marketing and backed by upper management.

The Revelation:

My friend’s idea: put an experienced salesperson in the role of the brand ambassador. Allow them to educate, entertain, illuminate on the virtues of the brand like an ambassador. But also: make sure they completely understand the needs of the customer and are responsible for getting a bottle on a shelf or bar, depleting it and getting a second one up in its place. They would have to understand distributor dynamics, pricing, motivation, clear goal communication and the myriad other details of selling. Last drink with a bartender at midnight; first meeting with a distributor at 9am the next day, first in line when the retailer opens at 10. But not selling product. Selling value. And this is where the entire industry was failing. It was growing a generation of product pushers leading and sticking with “facts”. No one was selling the value of the product.

Value: the combination of qualities that encompass worth, usefulness, desirability and choice.

Background

Two years before my entrance, I was a sales manager with a tech company called PeopleSoft. I convinced them to make a run for this same distributor’s business: adoption of a complete corporate systems make-over. We pitched a unified ERP, CRM, warehouse management, financial and HR systems overhaul. We were known for successfully implementing CPG, financial, manufacturing, tech and insurance companies, but this was our first booze business pitch. Our value pitch: we will unite all of your disparate departments and operations in one unified view of the corporation. Executives will spend less time chasing down information and more time making critical decisions affecting the success of the business.

It was a 10-month sales cycle involving multiple entities, departments and “houses” and it gave me an extraordinary insight into the financial, logistic, cultural and data lifecycle of the distributor tier of the liquor industry. It also baffled our most knowledgeable and top tier system analysts. “How in the hell does this industry actually survive doing business like this?” was one of our executive’s remarks after studying their sales process. We lost the sale, but I never lost the insight: this was gangster land. But not gangster as in illegal; gangster in that there were unwritten rules of commerce that were implied with every transaction.

I spent my first year as a “brand ambassador” in New York City for a tiny, startup company that made “artisanal” blended Scotch whisky. I learned about the three-tier system and all the myriad roles in it; the complexities of pricing, bill-backs, incentive programs and all the contortions associated with the hierarchies of distributors. I learned the names of buyers, bartenders and brand managers. I learned how to set up a tasting, conduct a staff training, in essence, all the mechanics of the role.

The next year I was made the national sales/marketing/brand representative for the brand in North America. I had one staff member: me, and I covered 34 markets in the US, with a few jaunts up to Ontario. The company had a unique and powerful value statement: “we’re breaking with the past, we’re doing something completely different because blended Scotch whisky had gotten boring. No one wants to drink something that bores them.” Following this were the details of the process and product portfolio, in that order. We did not lead with facts, we led with value. The facts merely backed the value’s proposition. It was now incumbent upon us to prove that value, that we could delight people when they drank blended Scotch whisky; this in turn would be valuable to our direct customers: the distributor first, then their customers, the on/off trade, then to the consumer.

This was our value statement, and the value statement is the key to any successful, long-term branding position. Products, described through a series of “facts”, come and go and resonate only in one part of the collective memory and human brain. But value is both personal and economic, it’s the heart of capitalism and the key driver of adoption and retention. And when value is delivered in the form of a story, it creates an indelible impact.

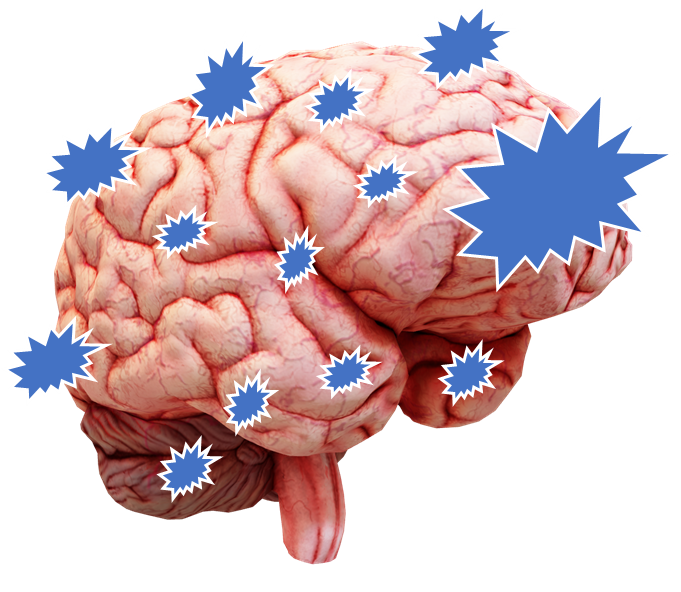

Your brain on “story”

This is your brain when it hears a story: it activates across the entire organ. When processing facts, only one or two areas activate: Broca’s Brain and Wernicke’s Area. The changes that take place when hearing a story are:

Neural Coupling: A story activates the part of the brain that allows the listener to translate the story into their own ideas and experience

Mirroring: Listeners will experience the same brain activity with each other and with the speaker.

Dopamine: The brain releases dopamine into the system when it experiences an emotionally charged event, making it easier to remember and with greater accuracy.

Cortex Activity: a well-told story can engage many different areas, including the motor cortex, sensory cortex and frontal cortex

Value: the combination of qualities that encompass worth, usefulness, desirability and choice.

At this time, the entirety of the liquor business came into perspective for me. I was in my 50s and had successful careers in other businesses selling value to those whose careers and businesses depended on it. Now, as an “outsider”, what I witnessed firsthand something both exhilarating and frightening. This was unbounded growth that caused a universal excitement, not just in the liquor industry, but throughout the general populace. At the same time, it caused an “irrational exuberance”, a chain reaction of unwise investment, myopic indulgence and a generation of “gatekeepers” motivated to keep all the “knowledge” wrapped up in a mystical box that they had the key to, so that they could increase their own worth, as subjective as it may have been.

Gatekeeping started with the new wave of bartenders, having been recently schooled in classic techniques of drink creation, bar management and the Pre-Prohibition drink culture of America and Europe. They were massaged by the brand ambassadors, ennobled by the salesmen, catered to by the drinks companies. They were given percs in the form of “competitions” that put money in their pocket and plane tickets to far off lands in their hands. All they had to do is advocate for the current brand of the day: put them in a drink, or on a menu or on the back bar. Tell their friends and “have one on us”. The bartenders morphed into “mixologists” before our very eyes, replete with moustache wax, suspenders and sleeve ties, now feeling obligated to shill for the last brand to hand them some cash. The simple Manhattan and Old Fashioned grew to Frankenstein-levels of unrecognizability, with each new “riff” on it backed by 3 different spirits, 6 different bitters and stirred by a branded spoon while under the gaze of a video camera.

Right behind them came the “journalist”, most probably an out of work English lit grad hanging out in bars looking for their next gig and tasting a Bees Knees for the first time. Some had gigs with established circular magazines like Esquire, Playboy and House and Garden. As reprints of ancient bar guides started to appear on websites and new books emerged tracing the history of just about everything (cocktails, whiskey, gin, bartending, etc) a new subculture took root: the spirits journalist. It didn’t take much to get published, all you really had to do is write up something you heard in a bar from a brand rep or bartender that sounded reasonably cogent and your pitch to the editor was ready.

While a handful of individuals emerged as actual professionals that fact-checked their stories and had editors with some sense of proportion and ethics, the entire digital and print universe was inundated with more words and pictures on a slice of life - spirit life - than had ever been written in the history of language. And underneath it all came the percs in the form of “brand education”: bottles, distillery tours, educational “vacations” and sponsorship at world-wide “bar conventions” which they would cover their brand for 1200 words and a few closeups.

After that came the “Competitions”, a rag-tag group of friends inviting other friends to “judge” a bunch of booze and give out awards to the “best”. This phenomenon came out of the wine industry, one of the greatest overreaches in consumer history: self-appointed experts jamming subjective opinions into an objective bottle and spewing out Gold, or worse, Double-Gold. The wine critic of the 90s, Robert Parker, popularized the 100 point scale of judging wines, and soon, the whiskey world, rum world and brandy world followed suit, each expert with their own score sheets, obtuse tasting notes and “Best of…” awards. Each one was done for a price and in the worst cases, as a for-profit business.

The cynicism had taken root in the industry and it became the norm. Gatekeepers were the inexpensive PR teams that could be had cheaply without having to put them on salary and give benefits to. Having gone through the boom and bust “tech bubble” of the 90s and early 2000s, seeing the obscene amounts of money spent for very little tangible return, I recognized this. Under these circumstances, this cannot last, there was going to be a reckoning. And I was only 1 or 2 years into it when this revelation came about.

Inability to sell value: This is the fundamental cause for the current downturn in the bev-alc industry. The growth was so fast, so unbridled that it changed the structure of the industry and those inside of it; while riding new technologies of social media and hyper-fast internet access, digging down into a value statement not only seemed too laborious and complex, but it was also rendered unnecessary, because no one else was doing it. Besides, who would understand it? The more time I take in crafting a value, the more chance I lose the space race happening all over the country: the whiskey and spirits sections of liquor stores doubling in on themselves, followed by the dedicated whiskey (or spirits) bars, buoyed by the cocktail renaissance. Once Bourbon got back on its feet and began sucking all the oxygen out of the air, a deeper cynicism set in: “these people will buy anything and at any price”. When that became the SOP, pricing followed, always wrapped up in “exclusivity” and commanding top dollar. Hello single barrels and small batches!

We went through waves of unaged whiskey stealing the romanticism of “moonshine”, all because they couldn’t wait, or afford, to age it, and selling it at $60 plus. Brand upon brand appeared, whether distilled on-site or blended from others, stealing some esoteric and obscure historical personage to build a flimsy story around. The flimsier the story, the higher the price. But at that point, no one knew what really constituted real “whiskey” whether it was Bourbon or Scotch. So a whole ecosystem of savants, de-coders, experts, geniuses and “journalists” arrived, to break it all down, to educate and enlighten. Propaganda Ministries…oh, sorry…marketing departments from the mega-giants went into overdrive, releasing wave after wave of brand variations, hiring and firing hundreds of willing “ambassadors” to fit the short expanse of budgets.

They were all supposed to educate the consumer, make it easier for them to get into the swimming pool; to get acclimated to the water and learn their first strokes. But that didn’t happen: there are still the vast majority of Americans that think all Bourbon comes from Kentucky and Scotch is not a “whiskey”. Instead of ensuring a new generation of informed consumers got into the pool, these gatekeepers and influencers stood on the edge with their arms crossed, setting up pass-gates for entry through their own subjective criteria, whether it was through a blog, a book, a social media post, a digital “listical” buying guide or some sort of “mastery” through a fake educational program that cost thousands of dollars to get some sort of “degree” to show your friends. Honestly, if I hear the word “master” again in relation to booze I’m going to shove a pie knife in my ears.

The Three Tiers

Make no mistake, the three tiers in the US are dominated by a monopoly: the middle distribution tier. Currently, there are 3 multi-state giants – Southern/Glazers (SGWS), RNDC and Breakthru – that are responsible for more than 60% of all distributed wines and spirits. They are all privately owned companies. The last I checked, SGWS was a $16B annual revenue. These companies, and the hundreds of smaller ones across each of the 50 states were born from the gangster eras of Prohibition, or before. Prohibition was meant to break the “tied-house” effect, where a supplier – beer, wine, booze – could directly affect the drinking habits of consumers by giving them things and conducting their own private capitalism rules. They had their own distribution routes, grocery stores, saloons, etc, and each led to its own type of gangsterism. One of the greatest scandals of the 19th century was the Whiskey Ring, a political action committee to re-elect the President; followed by the Whiskey Trust, a vast attempt to control pricing through intimidation. In the UK, the Distillers Company Ltd, - DCL – was a price fixing monopoly that eventually morphed – over 100+ years – into today’s Diageo. One of the romantic attractions to booze is its “bad-boy” halo, and this is where the halo grew to be a crown. When the US government kicked the can down the road and got out of business of regulating alcohol, the gangster traffickers of Prohibition all had a ready-made legitimate business – the middle tier, the pinch point in the hose. Everything must go through them or it doesn’t go at all. What could go wrong?

But that’s not to say it’s illegal or dishonest (although both of those vices occur). Some of the most honest and trustworthy people I’ve ever met work in this tier, including the friend who initially recruited me. But they all know their lives and careers are bound in a “gangster code of honor”. On top of that, the size and scope of the organizations contribute to its corruption: they live in a land of torpid resistance to change, bodies that are in motion and will stay in motion until diverted by an outside force. They’re like massive aircraft carriers stuck in a river canal: they can’t turn, they can’t pivot, they can only go forward at one pace. They have their own guilt of perpetuating the lack of value selling and have released two generations of “order takers” into the marketplace as they trade off stealing away the liquor giants as customers. The last of the great training programs in the booze biz was initiated by the old version of Gallo and one from Seagram. Both of these companies trained their distributors in the art of value selling. But that was over 40 years ago, and whatever institutional memory is left has been diluted and watered down by time, apathy and circumstance. There are smaller distributors in each state that still try to maintain a high sense of integrity, brand building and customer care, but in the face of massive monopolies that will roll over you in the blink of an eye, integrity can sometimes come at too high a price. As outliers, they fight an uphill battle.

Irrational exuberance causing too much inventory: “who’s going to buy all this stuff?”

While vodka, gin and some rums can be distilled and sold based on current market forces, aged spirits like whiskey, brandy and some rums have to run forecasts. The determination of what to distill today is based on forecasting what the market will be like when they mature. We’re currently floating in the sea of bad forecasting and cynical pricing scenarios as a result. Forecasting doesn’t happen in the warehouse, it happens in the C-suite offices. There are a number of reasons this has happened, pending the company, but this is why the term “irrational exuberance” is the proper lens to view it. Some companies are publicly traded and have a parade of executives that spin through those positions. Others are old-line family based organizations that hew to a more traditional, even conservative, view of the marketplace. But what’s showing now is a combination of greed, fear and reckless speculation, and those can affect even the most right minded individuals.

Consider this: In the US, a DSP (Distilled Spirits Plant) is a Federal license that allows an ethanol distilling operation to set up shop; a series of safety and systems checks that guarantee they won’t blow themselves up or poison people. And primarily, to be taxed. In 2000, there were approximately 60 licenses in the entire US: there were 8 legacy distilleries in Kentucky making bourbon; there were bottling plants and rectifiers throughout the US; there were ethanol factories like ADM and others, along with pharmaceutical/chemical producers, all granted a DSP, a license to distill.

At the end of 2023, the ACSA surveyed 3,069 DSPs in the US. Even when you break that down between actual liquor producers, rectifiers and bottlers, it’s still a mind-boggling leap (I’ll save you the math: it’s a 5015% increase).

Too little differentiation

Kentucky alone went from 8 to over 80 distilleries during that period. This does not count the increase in production in the existing legacy plants, which made headlines weekly. Given the strict definitions of bourbon that affect its flavor range, how much actual variation can be determined in its taste? As someone who’s judged and tasted thousands, I can tell you: very little. Mash bills and age are the leading flavor differences, but the thousands of nuances from bottle strength, warehouse position and the occasional secondary finish are like counting the number of angels dancing on the head of a pin. So in order to differentiate, you have to invent things, cynical things, irrelevant things. The story gets more and more threadbare because the deeper you go, the more it sounds like the other 30 on the shelf next to it and its actual value disappears. “So maybe, we just change the color of the typeface…” and voila! A new brand is born. At a higher price.

At the end of the 20th century, Ireland had only 3 functioning distilleries. It now has over 50. There are 4 styles of Irish whiskey: grain, single malt, pot still and blend. You have a little more wiggle room for flavor but a tasting survey of Irish whiskey suggests a uniformity of flavor.

Scotland, after shutting down approximately 25 distilleries since the 1980s “whisky loch”, now are brimming past 145. There’s more variance in Scotch whisky than other styles, from deep smoke to high fruit, so Scotch can still market by its variance and range. But given that most of the brands are owned by 2 corporate giants, each a master class in pricing cynicism, it risks pricing itself out of relevance.

Japan had 2 distilling giants: Suntory and Nikka, and a dozen or so other shochu plants, mostly all selling to their domestic market. There are now close to 200, by some estimates. What saves Japan is its internal methodologies guided by the rules of kaizen and the discipline of its supply chain.

India’s growth is off the charts; Australia/NZ have quadrupled their output, etc., etc., so we have no way of knowing how this affects current or future supply.

Taking into account all of the “non-distiller brands” that buy, blend and bottle existing aged spirits and you have an explosion that defies any sort of common sense, never asking the question: who’s going to buy all this stuff?

What would cause this? An ambitious dentist or a disenchanted portfolio manager could each start a distillery with an overabundance of passion and zero market skills. But their individual impact is small, even when multiplied. The entire sector of “craft” distilling tipped the scales quite a bit, but each new entry into the marketplace made more of a local or regional impact, if they’re fortunate (“How do I make a small fortune? Start with a large one”). While the overall impact has grown over the past 10 years, they still are dwarfed by the massive multi-national supplier companies: Diageo, Pernod-Ricard, Bacardi, Constellation, and to some extent ABInbev. If any change is going to be made in the alcohol industry, it has to start here.

All the other reasons that people are pointing to, from tariffs to marijuana to the fiction that “Gen Z doesn’t drink” are are lamplights that showed up at the same time to exacerbate an issue that has deep fundamental problems. But the press, not knowing what they’re talking about, insist on focusing on them as the main issues. And with that, it’ll never get solved.

Solutions:

Instead of drawing back out of the market place, suppliers need to double down on advocacy. But you can no longer to afford to hire just a “brand ambassador”. This person has to be trained in sales methodologies and more importantly, compensated like a sales person: tied to the top line of revenue generation. Otherwise, they’ll continue to be a “cost”, a marketing program that blows with the winds of change.

The entire distribution sector is in need of a shakeup. That won’t be easy and the last thing we want is the government getting involved to do it. Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) laws are being passed state by state, allowing in-state-oriented suppliers to ship directly to consumers without stopping in the distributor tier. This is the first challenge to the monopoly since Repeal. But they’re here to stay for the foreseeable future, they own casino everyone else has to play in, so change has to come from within, and it will be generational in scope. The first thing they can do internally is commit themselves to train their salespeople in the value sale. Good luck with that.

The large multi-nationals need to break up. There is no good reason on Earth for a Diageo to exist, it literally adds no value to the sector except for its shareholders. For every small innovation, they counter it with market recklessness on a scale of 10x. Pernod-Ricard needs to recapture its great strength of brand building. Remember, this company saved both the Irish whiskey industry and the Canadian as well. Would it be that they can recapture some of this forward, progressive thinking. Constellation is where brands go to die, so what’s their point in existing? And for god’s sake, please keep private equity out of the equation.

Demote the gatekeepers. Unless they’re committed to actually putting the truth out into the public sector, they need to collectively STFU unless they have something of value to share, not just getting paid or strutting around.

Stress experimentation and easy access. Bring back the idea of the metaphorical “highball”: forget the #hazmat and overproof formats. Make booze easy and fun, not a feat of strength for Spartacus.

Coming up: Route to Market Class for Brands:

Moonshine University in Louisville, KY is one of the leading educational sites to learn how to distill, quite literally from grain to glass. Everything a distiller needs to know to create their own product.

At the same time, they’re focused on the health of the product when it hits the market. I’ll be revising my 2-day “Route to Market” class there on January 29-30, 2026. Here’s a link to register: https://bit.ly/MoonshineU